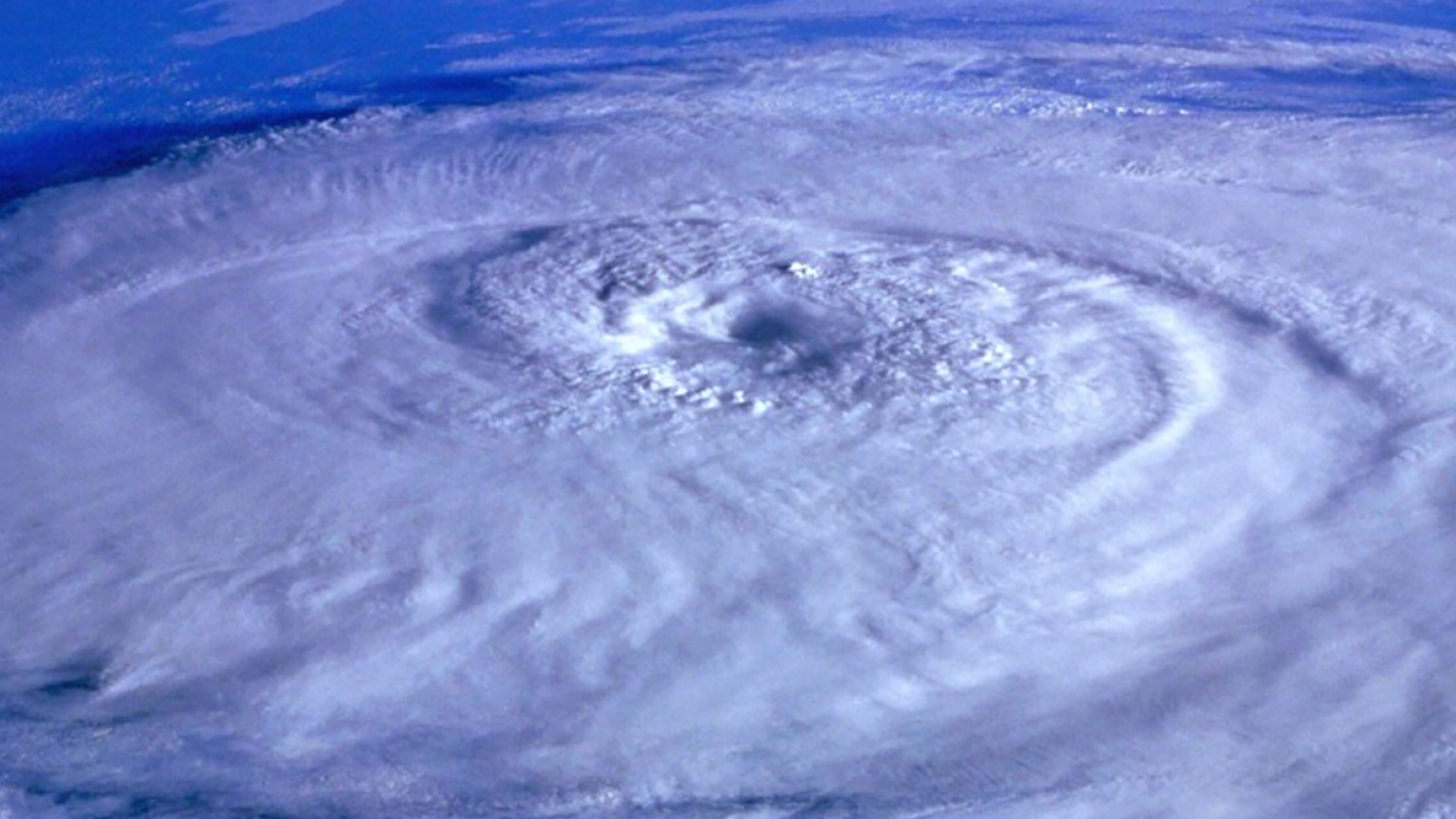

Can Hurricane Melissa lead us to real change at COP30?

Hurricane Melissa reminds us to get serious about poverty reduction in a raging climate. Can the path of a record-breaking hurricane lead us to real change at COP30?

With grim timing, one of the most powerful Atlantic hurricanes ever recorded has swept through the Caribbean, just as the international community prepares for the next stage of deliberations over climate action at the COP30 climate summit.

The scale of the devastation – forcing tens of thousands of people to take refuge in emergency centres – is an emphatic demonstration of why we need to take meaningful steps on climate action.

As families in shelters figure out how and when they can return to their homes across the Carribbean, speaking up for poor people in the face of the climate crisis everywhere is vital. Although the challenges of inequality, environmental degradation and poverty intersect, they are often seen and treated in isolation, leaving us trapped in fragmented thinking. In climate summits, the mitigation of emissions has taken centre stage up to this point.

It’s time for this to change. The COP30 President Designate, André Aranha Correa do Lago, and Bill Gates have recently both made powerful statements about how development and adaptation are interrelated and mutually reinforcing; Gates even argues they’re the same thing. The outcome of any climate talks must ensure that the needs of the poorest communities are met.

Until recently, reliable data on the scale and interconnections between poverty and climate have been scarce, making effective action even harder. New data to close that gap have just been published by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This edition of the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) identifies regions – in predominantly developing regions – where poor people face overlapping environmental hazards such as high heat, air pollution, floods or droughts.

The overlap between poverty and environmental hazards is surprisingly clear. Of the 1.1 billion poor people worldwide, 887 million are exposed to at least one climate hazard. Most face more than one: 651 million experience two or more hazards, and 309 million face three or four. In all the countries and subnational regions covered that are affected by one or two climate hazards, on average one in seven people (14.4%) are multidimensionally poor. But in regions in which three or four climate hazards struck, it’s one in four (24.8%).

We also know from the global MPI that middle-income countries are a hidden epicentre of both poverty and climate hazards. Nearly two thirds of all multidimensionally poor people live in middle-income countries (64.5%), including 100% of the poor people in Latin America, Europe and Central Asia. A climate lens reveals that middle-income countries also carry a heavy climate burden: in lower middle-income countries 548 million poor people are exposed to one or more climate hazards (88.0% of all poor people) and, in upper middle-income countries, it’s 93 million (91.1%). This is higher than for low-income countries where it’s 246 million (61.3%).

Many worry about the climate on behalf of their children or grandchildren. But this study reminds us that climate hazards are already here on a large scale. In October alone, it’s not just Hurricane Melissa; flooding, for example, has also disrupted lives in countries including Mexico, Honduras, Viet Nam, India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Nigeria. With clear statistics, solidarity and informed policy action, climate hazards can, and must, be addressed. We look forward to what COP30 can achieve. It is clear that multidimensional poverty measurement must be included in its metrics for adaptation. The experiences of poor people must be included in the future of global climate policy.

Discussions on adaptation finance will need to address the growing gap that the UN Secretary-General has pointed out is more than 12 times greater than the finance they receive today, with a deadline of 2035. We hope any adaptation financing focuses on the suffering of poor people and the human impacts of interventions or inaction. As leaders and delegates converge in Belém, COP30 provides an opportunity to confront the current human cost of climate hazards with compassion and determination, in alliance with the communities most affected.

Carlos Alvarado Quesada is the former president of Costa Rica (2018-2022), and Sabina Alkire is the director of the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative at the University of Oxford.