What Brexit and the election of Trump can teach us about the politics of emotion

Analysis of social media posts during two recent periods of intense contestation sheds light on how political actors make use of emotion to mobilise support.

We live in an era when political discourse is rife with emotion. Fear and anger feature most prominently, from anxiety about global calamities such as climate change and COVID to offence-taking in the face of polarising rhetoric around race and culture. So we need to gain a better understanding of how political actors make use of these emotions.

In a new article, we explore this question in relation to populist and governmental actors, asking who is more prone to stoking anger and who is more prone to fomenting fear? We do so through an analysis of social media posts during two recent periods of intense contestation and political crisis: the 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK and the 2016 election of Donald Trump in the US.

Who stokes anger, who foments fear?

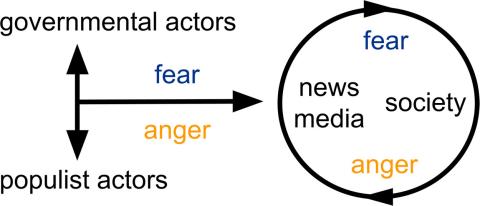

We started from the hypothesis that in a contest for media attention and the hearts and minds of citizens, populists tend to pursue a politics of anger, while establishment politicians pursue a politics of fear. The news media and citizens, at the aggregate level, tend to pivot either towards the establishment politics of fear or towards the populist politics of anger. We call these processes “fear-anger contests”.

It seems likely that fomenting fear comes naturally to governmental actors because, when fear takes hold, people “rally around the flag” and “follow the leader,” accepting that “there is no alternative” to the status quo. Fear makes people risk-averse and deferential.

Meanwhile, populists are more likely to stoke anger because populism is about disrupting established elites, and it takes anger to do so. Angry people do not accept that “there is no alternative” and see fearful people as misguided and part of the problem.

There is considerable evidence in the academic literature to support this – for example, one survey-based study on far-right voting in France after the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks found that anger was associated with voting for the Front National, while fear was associated with voting against it. Other studies have associated Donald Trump with populist anger. And yet some thinkers, including public intellectuals such as Martha Nussbaum and Michael Moore as well as some academics, have associated populism with fear. And many will take it as a truism that populist politicians like Donald Trump and Nigel Farage, or populist news media like Fox News and the Daily Mail, foment fear.

We were also interested in exploring the relationship between fear and anger. Psycho-evolutionary theory and appraisal theory suggest that fear and anger are polar emotions although they clearly have important commonalities. So our research tested the hypothesis that there is a negative correlation between fear and anger in media and society; when news media are more receptive to fear we expect them to be less receptive to anger, and vice versa.

Model of fear-anger contests

Fear-anger contests in the context of Brexit and the Trump election

To test our hypotheses in the contexts of Brexit and the election of Trump, we generated Twitter datasets for three entities: political actors (“Remainers” and Democrats on the one hand, “Leavers” and Republicans on the other), the news media and society. We then measured the emotional content of their tweets. We also created time series that allowed us to correlate fear and anger levels and establish whether these correlations were positive or negative.

We examined the tweet content through automated sentiment analysis, using machine learning and emotion dictionaries. Sentiment analysis measures the polarity, often along a positive-negative axis, of opinionated pieces of text. In this study we focused on emotion classification, which considers multiple, possibly continuous or discrete axes indicating the salience of different emotions like fear and anger, rather than a positive-negative axis.

For the machine learning approach, we used a model provided by Colnerič and Demšar. The authors retrieved a large set of 73 million tweets, filtered the set for tweets containing emotional hashtags and using Plutchik's wheel of emotions, and mapped the hashtags to different emotions. This provided ground-truth emotion labels for training a neural network.

Dictionary-based approaches represent mappings between words and some kind of sentiment or emotion value. Given a text to be classified, the words contained in it are matched against the words in the dictionary. The words’ corresponding sentiment values can be aggregated and used in various ways. We used WordNet Affect, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, and the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon.

We validated our empirical findings by conducting significance tests to ensure 95% confidence throughout.

Brexit conforms to expectations; the Trump election brings a surprise

In the case of Brexit, the data indicated a fear-anger contest that closely conformed to our theoretical expectations. During the referendum campaign, politicians in the Remain camp used more fear-based rhetoric than politicians in the Leave camp most of the time. Conversely, politicians in the Leave camp used more anger-based rhetoric than politicians in the Remain camp most of the time. To put it colloquially: Remain approximated “Project Fear” whereas Leave approximated “Project Anger.”

If the UK Brexit referendum presented a contest between “Project Fear” and “Project Anger” that closely aligns with theoretical expectations, then the election of Donald Trump presented another type of fear-anger contest that departed from some aspects of the model while conforming to others. Our data indicated there was a neck-and-neck race between Democratic and Republican politicians when it came to expressing fear and anger, with either side sometimes in the lead.

For example, among Democrats, anger levels shot up when Trump called for a travel ban against Muslims. Among Republicans, anger levels reached a peak when Clinton called Trump supporters “deplorables.” Thus instead of a contest between “Project Anger” and “Project Fear,” as in the case of Brexit, we found a general negativity contest. While both parties reinforced each other's negative emotions, to our own surprise we found that, overall, Democrats led on both fear and anger.

Although this failed to prevent Trump's victory, even after the election governmental actors persisted in depicting President Trump as a threat, for example to democracy or free trade. To counter this, Trump and his allies angrily denounced this as a “witch hunt.” The continuation of fear-anger contests when populists are in power presents an interesting avenue for future research.

The relationship between fear and anger

As regards the relationship between fear and anger in the media and among the public, we found support for a negative correlation in the case of Brexit, whereby fear levels declined as anger levels rose, and vice versa. In the case of the Trump election, we found only a weak inverse correlation between fear and anger levels in the news media.

In our society sample in the Brexit case, we saw a crescendo of fear from February to April 2016, followed by a decline in May and June. This decline of fear in the final two months of the referendum campaign may have contributed to the defeat of Remain, as it may have emboldened Brexit-leaning voters to vent their anger and vote Leave.

The question of which political actors rely more on fear or anger, and how fear and anger resonate in media and society, is of great salience in a time and age when political discourse is rife with emotions. This was evident again in the 2020 US presidential election, and it is destined to remain an issue. We call for further research exploring the interplay between the politics of fear and the politics of anger.

Further information

Jörg Friedrichs, Niklas Stoehr and Giuliano Formisano (2022) 'Fear-anger contests: Governmental and populist politics of emotion', Online Social Networks and Media 32: 100240