Reforming the global financing development framework to serve the world’s poorest – opportunities for the FFD4 Conference in Seville

Starting today, the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) takes place in Seville. Held every ten years since 2002, this iteration of FFD comes at a potentially pivotal time for multilateralism in a world reeling from aid cuts, tariffs and trade barriers, inflation, low growth, conflict and climate shocks. The pressure for significant and strategic reforms is mounting.

Investing in national data systems, collection and skills is essential for supporting a renewed global financing framework. Presentation on the MPI by the National Statistical Office of Burundi (INSBU) to the Technical Committee of the Statistical Information (CTIS) in Burundi, 2025.

Since its inception, FFD has served as the primary forum within the UN calendar to bring together an array of stakeholders in international development to discuss the whole edifice of the prevailing international financial architecture. This means a broad base of high-level leaders and delegates in public and private finance; government and development-related ministries; as well as businesses, international organisations and civil society.

This year, the FFD conference aims to generate high-level commitments and catalyse plans for reforms on delivering two main goals: a ‘large scale impact focused investment push’ for the SDGs and ‘reforming the international financial architecture’. These are ambitious, wide-ranging and multifaceted topics that have the potential to course-correct global development for the next decade. So, among the aspirational headlines and technocratic discussions, what can measurement tools like the Multidimensional Poverty Index or MPI – which our research centre, OPHI, works on – offer in this space?

Metrics are more important than ever for poverty reduction in 2025

Multidimensional Poverty Indices, both national and global, provide key contexts for discussions of development financing. If we take first the push to renew investments for SDG impact: only 17% of the SDG targets are on track. When it comes to the SDG target for multidimensional poverty, between one half and two thirds of the 62 countries reporting trend data in the global SDG databank in 2024 were not on track to halve the incidence of multidimensional poverty by 2030 if current trends continue.

We know that this reflects a world where 1.1 billion people are living in acute multidimensional poverty – deprived in basic indicators related to their health, education and living standards. Our global Multidimensional Poverty Index – co-published with the United Nations Development Programme – shows that in 112 countries, home to 6.3 billion people, half of all the 1.1 billion multidimensionally poor people are children. Globally, 84% of poor people live in rural areas; 48% of poor people live in Sub Saharan Africa, and 35% in South Asia. These shares already highlight clear pathways for focused investments.

But the annual financing gap for financing sustainable development has risen from $2.5 trillion from before the Covid-19 pandemic to $4 trillion, largely – it’s said – because of underinvestment and increasing development needs. The largest underfunded gaps are in sanitation, energy and water. We find this sobering. We know from the global MPI that 828 million MPI-poor people lack adequate sanitation, that half of all MPI-poor people lack electricity (579 million) and that nearly half again are deprived in drinking water access (513 million). We also know that among other deprivations, 637 million poor people live with a person who is undernourished in their household and 590 million poor people live in a household where no one has completed six years of schooling.

So, what is to be done? Global MPI data tracks the level and indicator composition of multidimensional poverty in detail for 1,359 subnational regions, by age, area and gender of the household head among others, providing actionable information that can create rapid and life-giving change. As has been well documented, the worrying scenario of SDG underinvestment is being compounded by a precipitous decline in Official Development Assistance (ODA). This decline reflects the failure of developed countries to honour their promises of 0.7% of Gross National Income and has been catalysed this year by cuts by advanced economies led by the US, with serious implications for the developing world. The ODA tide has been going out all year stranding multiple life-saving and essential development projects. However, the shakeup of the main contributors to ODA and innovations in funding models to be discussed at FFD4 could rescue the situation. An adage is rapidly gaining ground, ‘doing more with less’, but doing more with less still requires data, and tools like the Multidimensional Poverty Index, MPI, are critical to help identify where to target long-term investment – whoever the funders might be.

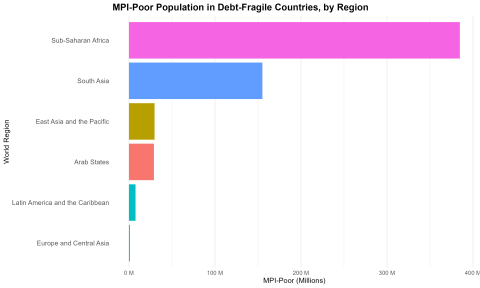

The MPI can also add context to another key theme of FFD4. The topic of debt reform returns to the financing framework agenda this week. Sixty-one developing countries now spend 10% or more of their government revenues just on interest payments and in 2023 developing countries spent a record $1.4 trillion servicing external debt, the highest in 20 years. Over 40% of people living in extreme monetary poverty live in countries facing severe debt issues. Based on the same criteria, we find that 56% of the multidimensionally poor measured in the global MPI are living in a country with debt fragility (607 million people). (‘Debt fragility’ is defined as having at least one of: a Moody's credit rating “substantial risk”, “extremely speculative” or “default”; a debt sustainability analysis risk rating of “in distress” or “at high risk of debt distress"; a bond spread of more than 1,000 basis points). There are an estimated 385 million MPI-poor people living in debt-fragile countries in Sub Saharan Africa and 155 million MPI-poor people living in South Asia.

Source: Calculations by Niall Maher based on Table 1 Alkire, S., Kanagaratnam, U., and Suppa, N. 2024b. “The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) 2024 Disaggregation Results and Methodological Note.” OPHI MPI Methodological Note 59, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford, UK.

The Vatican recently launched a report by the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and Columbia University focusing on debt reform in ‘a Jubilee year’ when traditionally the Catholic Church focuses on forgiveness of debts and tackling injustice and inequality. In the 2000 Jubilee year, over $100 billion in international debt was cancelled. However, a lack of structural reform together with the vicissitudes of the global economy seem to have undermined those gains. Governments, already hard pressed to service debt, risk spending less on their development commitments when faced with ODA funding pulling out. It is therefore clear that we need widespread reforms, including restructuring debt for the countries currently affected – as well as reforming the lending system with longer maturities on loans and low-cost borrowing.

Renew multilateralism through ‘coalitions of the willing’

At FFD4, the Sevilla Platform for Action (SPA) will mobilize alliances of countries and stakeholders for specific initiatives. The Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty, of which we are proud to be a founding member, is commended the in FFD4 outcome document, the Compromiso de Sevilla, because of its focus on addressing the fragmentation of finance for poverty and hunger eradication. The alliance promotes country-owned and led integrated approaches, greater cooperation among international organizations, national governments, parliaments, financing institutions and other stakeholders and strategic coherence across all forms of interventions. It is a step in the right direction.

We are also thrilled by the prospect of the launch of the Beyond GDP Global Alliance to help support the evolution of metrics that ‘reflect progress on the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development’. In a world of inequality and climate change, perspectives that can focus global attention on the implications of traditional economic growth are essential and potentially transformative. At OPHI we believe that multidimensional measures of poverty and well-being should be considered as part of the Beyond GDP initiative to track development progress on a shared planet and we are delighted to be members for this initiative too.

Invest in national data collection and statistics

Data and metrics are the lifeblood of action circulating to nourish and refresh policy interventions on poverty with tangible and up to date information. Data show when and where to invest in interventions and when to celebrate and learn from significant poverty reductions. Multidimensional poverty data in particular has great potential to improve the cost-effectiveness of interventions to eradicate poverty. The Compromiso de Sevilla rightly devotes a section to data collection and statistics. It focuses on strengthening national data systems which experienced unprecedented shocks this year with the cuts to USAID. To illustrate the importance of this, earlier this year, Kenya’s Ministry of Health lost access to its Electronic Medical Records because the data were physically hosted by a server operated by a partner that was funded by USAID. Addressing the precariousness of existing systems in developing regions is a clear priority for investment.

Another key priority to drive accurate poverty reduction is supporting the household survey. MPIs rely on high-quality household survey data. Many less developed countries lack the necessary funds to field their own surveys regularly and rely on international survey systems such as UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, which themselves are funded by sources that cannot currently be guaranteed. The fate of the Democratic Health Survey programme for instance, which was stopped by USAID, waits to be decided. We hope that household surveys are a key element of investment in the next ten years. In the words of the Inter-Secretariat Working Group on Household Surveys, surveys are ‘a necessary foundational data source’ of basic demographic and health data in all countries, especially in many low- and middle-income countries’. And these must not ‘must not rely on a single donor but instead be backed by a broad coalitions of development partners who share a common vision of strengthening national data systems.’

Progress for global development that serves the world’s poorest needs global cooperation with inclusive coalitions of new, committed and cooperating actors. And it needs a lifeblood of data on who is poor and how they are poor by core social and economic indicators, so that limited resources can have the most impact. We hope that FFD4 will be a turning point where words were converted into transformative action and commitments that truly paved the way for development progress.

Many thanks to Niall Maher for the analysis of debt fragility