How special interest groups capture trade policy in Pakistan

New empirical research examining what drives trade protection in Pakistan finds that sectors with exposure to politically powerful businesses have disproportionately benefitted over the last 20 years, through a complex mix of tariff and non-tariff measures.

Pakistan has one of the most protectionist trade policies in the world. A recent report by the World Bank has argued that the country’s trade policy has an anti-export bias, since by affording greater import protection to businesses it incentivises production for domestic rather than export markets.

However, we have little knowledge of where the demand for such trade protection comes from. Is it driven purely by economic objectives or is there also a distinct political logic behind trade protectionism? In particular, are sectors exposed to powerful business families and politically connected actors more likely to receive higher trade protection compared to politically unexposed sectors?

This question is particularly important for three reasons. Firstly, Pakistan has witnessed substantial tariff liberalisation since the late 1990s as tariffs have fallen from 55% in 1998 to 12% in 2021. Despite such liberalisation, there is a significant variation in effective protection rates across sectors. Previous studies have hinted that such variation might be explained by differences in lobbying power. However, this remains to be empirically verified. Secondly, in the wake of its recurring balance of payments problems, Pakistan has frequently tried to reduce its imports by resorting to emergency trade measures, such as the imposition of ad-hoc duties on imports (e.g. regulatory duties). Thirdly, the process of trade policy formation in Pakistan is usually ad-hoc, complex and non-transparent. Trade policy is riddled with exemptions and exceptions. This leaves considerable scope for discretionary application of trade protection. All of this provides a strong indication that trade policy might be tilted towards sectors with established businesses who possess greater political capital and lobbying power.

Mapping politically connected actors

To investigate the politics of trade protection, we compiled a granular database on the presence of politically connected actors in 119 manufacturing sub-sectors of Pakistan. Our political connections dataset maps information on the presence of trade associations, parliamentarians and their business interests, and politically entrenched business families in Pakistan. We combine this political database with product-level data on various measures of trade protection, including tariffs, regulatory duties, additional customs duties, and non-tariff measures (NTMs). Our dataset spans the last two decades covering the period, 1996-2021.

We then utilise this data in an empirical strategy that leverages a change in political leadership in 2013 that brought a pro-business political party to power, which signed an IMF programme whose key conditionality centred around trade reform. Coordinating with other multilateral donors, such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, the IMF insisted on simplification of tariffs, elimination of statutory regulatory orders (SROs), and the removal of non-tariff barriers (e.g., quotas and restrictions). While the government of the day sought to comply with these requirements, it resorted to other compensatory forms of trade protection. Consequently, the year 2013 saw a major wave of regulatory duties and non-tariff measures. This affected almost all manufacturing sub-sectors. For example, while in 2012 less than 10% of total products in the manufacturing sector were covered by NTMs, the ratio increased to 80% in 2013.

We leverage the timing of this change in political leadership and an externally driven attempt at trade reform in a difference-in-differences regression framework and investigate whether manufacturing sub-sectors that were exposed to politically influential businesses ended up receiving a disproportionately higher level of compensatory trade protection compared to politically unexposed sectors after 2013 (relative to before). The results are instructive. We find that sectors with prior exposure to politically powerful businesses disproportionately benefited from higher regulatory duties after 2013. A similar pattern holds true for non-tariff measures. Sectors exposed to special interest groups (SIGs) represented by strong business lobbies or politically connected firms received a higher intensity of non-tariff protection in the wake of the 2013 trade policy shock.

Obfuscating liberalisation

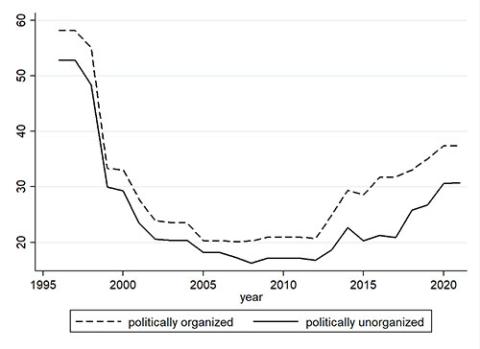

To take a broader empirical sweep at this political economy of trade protection, we estimate a structural model of trade protection that accounts for the role of government-industry interaction in the presence of SIGs. Our results affirm that the presence of SIGs and politically connected actors was an important determinant of the equilibrium level of trade protection in Pakistan. Precisely, we demonstrate that the effect of SIGs kicks in during the post-2008 period, and is amplified after 2013. Our results also reveal a curious empirical pattern that suggests a reversal of trade liberalisation during the two decades that form part of our study period. Thanks to declining tariffs, overall trade protection registered a steep decline after 2001. However, the introduction of alternative trade instruments compensated for this fall in tariffs in the following two decades, restoring overall trade protection to the same level as in 2001. Differentiating these patterns by exposure to political influence, we show that politically exposed sectors ended up receiving even higher trade protection than was available to them earlier in the liberalisation period (see Figure).

The evolution of overall trade protection in Pakistan 1996- 2021

Source: Author's data

This empirical analysis, which was conducted for the Research for Social Transformation and Advancement (RASTA) study at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, carries profound implications for understanding the role of political economy factors in trade policy formation in developing countries, in general, and Pakistan, in particular. Our results highlight a partial and hesitant process of trade liberalisation where tariff reductions were followed by the introduction of less transparent instruments of trade protection that effectively “obfuscated” the process of liberalisation by making it more complex. A complex trade policy, in turn, seems to have benefited politically influential businesses.

A drag on development

It is important to emphasize that while the political capture of trade policies is particularly evident after the rise of the PML(N) party to political power in 2013, it continued unabated despite the change of government and the arrival of Imran Khan’s PTI. Such policy continuity highlights the continued access of vested interest groups to levers of power. While political parties compete on the electoral stage through different narratives, the core elite interests are protected regardless of whoever is in power. Public policy debates in Pakistan routinely invoke the term “elite capture” to describe the politics of policy. Our work provides a concrete empirical illustration of how such elite capture works in practice in the context of trade policy.

There are also more concrete implications of this research for public policy. The import protection afforded to special interest groups entrenches the anti-export bias of Pakistan’s trade policy, which is considered a major drag on development. In fact, import protection is fundamentally connected with Pakistan’s core development challenges, including stagnating exports, declining productivity, and recurring current account imbalances.

Pakistan’s inefficient policies for import protection support an archaic trade policy regime that effectively functions as a disguised import licensing system, which favours more established and politically influential firms. To address the country’s myriad development challenges, Pakistan needs to adopt a simple and transparent trade policy regime. It also needs to discard the use of trade policy for revenue generation. Globally, on average only about 2.3% of total revenues are raised through trade taxes. The corresponding ratio for Pakistan still stands at 12%.

Further information

Adeel Malik and William Duncan (2022) ‘Obfuscated liberalization: how special interest groups capture trade policy in Pakistan’. In Nadeem Ul Haque and Faheem Jehangir Khan (eds) RASTA: Local Research, Local Solutions, Political Economy of Development Reform, Vol VI, Research for Social Transformation & Advancement (RASTA), Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabadc