Forging new lives: Congolese refugees as digital creators

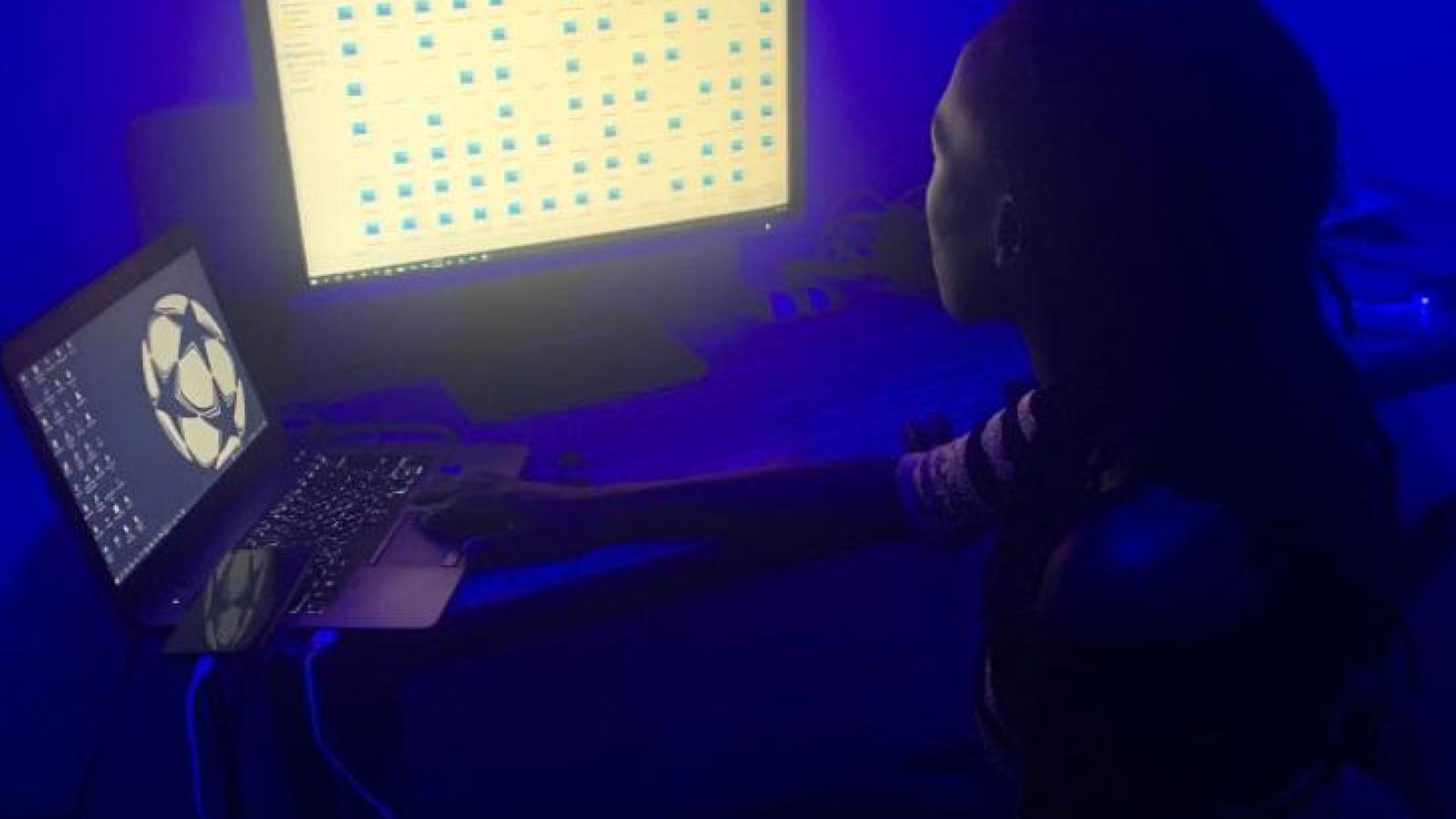

From supporting widows to promoting comedy acts, innovative YouTube channels launched by refugees in Nairobi are helping them gain both an income and a sense of belonging.

In an increasingly digitised world, online work offers a pathway to improve socioeconomic development and reduce unemployment for both refugee and host communities. Digital labour and e-commerce platforms hold significant potential for creating new jobs, especially among young refugees, as access to formal employment is often very limited. This trend has increased since the Covid-19 pandemic, fuelling new scholarship on digital livelihoods among forcibly displaced refugees. However, few studies examine how refugees are already making use of digital technologies and social media platforms to make a living. Our research addresses this, exploring how Congolese refugees create YouTube channels to earn a living in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi.

With one of Africa’s most advanced digital infrastructure networks, Kenya offers increasing digital economic opportunities, not only for refugees but for young people in general. Even before Covid-19, refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) had launched YouTube channels, but these have proliferated in the post-Covid period, following social isolation requirements and people’s inability to access work. As a result, YouTube channels have become a new form of online business.

The struggle for the right to work

According to the UN High Commission for Refugees in 2022, around 91,000 refugees and asylum seekers live in Kenya’s urban areas (mainly in Nairobi) – approximately 16 per cent of the country’s total refugee population. A new Refugees Act, effective from February 2022, provides more opportunities, rights and protection for refugees and asylum seekers. However, in practice, significant obstacles to refugees exercising their right to work persist. Lacking identity documentation, many cannot access the formal labour market, open a bank account or use mobile money systems under their own names, meaning most work in the informal economy.

Congolese refugees’ entrance into the digital world often follows negative experiences in the local labour market. For many who are highly qualified, whether having gained skills in their country of origin or through the Kenyan system, these barriers often push them to consider alternative economic opportunities via the online world. Our fieldwork in 2021-2022 identified 70 YouTube channels founded by refugees living in Congolese-concentrated areas in Nairobi. Based on this mapping, we conducted 20 in-depth interviews with YouTube channel owners, following them online and offline to gain understanding of their activities and how they shaped their lives.

'Refugees carry their talent with them'

One such channel is Bortopra TV, a community channel established by a former student from South Kivu in the DRC “to inspire and empower young people towards their dream”. He arrived in Nairobi in 2015 aged 25, with nowhere to stay. Forced to accept any job he could to survive, he soon resented working under exploitative conditions and decided to dedicate more time to developing his own social business. He established Bortopra (derived from “Born to praise”) on YouTube in 2017, explaining: “It is a platform that we give to refugees to show… what they can do, to showcase it to the world, because here, as you know, refugees do not have access to media houses. But refugees did not leave their skills and talents back home. They carry them with them.”

The stories behind why refugees embrace the digital world indicate that it is not only to make a living, but also to challenge narratives about refugees “being a burden” to the host community, by creating a safe space where hosts and refugees can interact. Several YouTubers have two channels, one in English or Swahili, another in the Congolese language of Kinyamulenge, hoping not only to interact with their communities, but also to drive change about how they are perceived and connect with other communities, including Kenyans and other refugees in Nairobi.

Beyond the online-offline divide

Our study also showed there is no clear-cut dichotomy between the online and offline worlds, as is often portrayed in literature on Livelihoods 2.0 and refugee self-reliance. Often, the new businesses that connect refugees to the global economy are also intertwined with the local urban economy – as shown by a YouTube channel called Icizere TV (“hope” in Kinyamulenge), established by another refugee from South Kivu, widowed soon after her arrival in Nairobi in 2016. Her channel tackles stigma around being a widow in the community. “There are many [widows] who are educated and have what it requires,” she noted, “but still, they have that fear of standing on their own. That is what I envision: to empower the widows in the community… through my channel’s shows.”

Besides her YouTube channel, Icizere TV’s owner has a shop selling clothes and phone accessories. Her online presence has increased her popularity within the community, expanding the clientele at her shop. Some of the shop’s profits are invested in her YouTube channel to produce videos that will drive growth. Although the channel is not yet monetised, she has increased her income due to her investment in the digital space.

A range of non-digital economic activities takes place around the production of YouTube channels. For instance, the Kanyamukwengo Comedian YouTube channel is a profitable business both online (with almost 50,000 subscribers and over 5 million views) and offline, with community members inviting actors on the channel to perform at events such as weddings. Content creators often develop related businesses, such as training others to become YouTube influencers, offering video editing services to both refugees and locals, renting out their materials or managing channels.

Bringing recognition and belonging

Despite a long tradition of research studying the role of remittances from a refugee diaspora perspective, research that focus on the connections between diaspora members living in countries of resettlement, countries of refuge and countries of origin is still rare. Our work aims to contribute to this growing field of study on diaspora economics from an anthropological perspective. YouTube channels in Nairobi can be sponsored, led or even co-led by someone in the diaspora. For instance, the Papa Legend TV channel is owned by a Congolese refugee resettled in the United States, who produces films about Banyamulenge culture. Diaspora members can also facilitate the registration and monetisation of these channels, sometimes charging for these services, taking commissions or offering use of their bank accounts for financial transfers via Western Union, WorldRemit or mobile money.

Most Congolese YouTube channels create content that can be viewed by people who speak similar languages, connecting viewers in Nairobi, DRC, Rwanda and Burundi, along with many in the United States, Canada and Australia. This increased audience brings economic benefits and helps shape Congolese refugees’ sense of belonging to “an imagined Banyamulenge family”. The YouTube space has become a place of recognition, both locally and transnationally, where refugees connect with the nearby and wider diaspora. Beyond opening new socio-economic opportunities, this enables many to consider Nairobi as a place they can make a living and start calling “home”.

The time and money refugees invest in online spaces indicates that they are not just about financial income, but also about aspiration and representation. This does not mean digital livelihoods are without problems. Different patterns of exploitation occur due to restrictions refugees face in Kenya, and You Tube’s algorithm itself creates new forms of inequalities among refugees. Yet Congolese refugees are successfully using digital channels to make a living and to create a transformative space in which they can expand their agency. These platforms offer a new way to exist – as one Congolese YouTuber put it, allowing “You-to-Be”.

Ghislain Bahati is a refugee from the DRC, living in Nairobi and employed as a Community Outreach worker by HIAS Refugee Trust of Kenya. Since 2017, Bahati has also worked as a research assistant for the Refugee Economies Programme based at the University of Oxford, as well as for Tufts University (USA). Bahati is a refugee’s rights advocate, founder of a Refugee-Led Organisation (RLO) called Kintsugi and chairman of the RLOs of Kenya (RELON-Kenya).

Dr Marie Godin has recently received funding from the University of Oxford’s Social Sciences Division Integrated Impact Fund for further research into “The Digital refugee Economy in Nairobi (Kenya): Opportunities, Challenges and Ways Forward”, in collaboration with the Refugee-Led Organisation Youth Voices Community.