Film, fiction and social change

A recent ODID roundtable profiled uses of film and literature in research in ways that place culture in conversation with the social sciences, use it as a medium of academic communication, storytelling or knowledge production, or deploy it as evidence of political or social change.

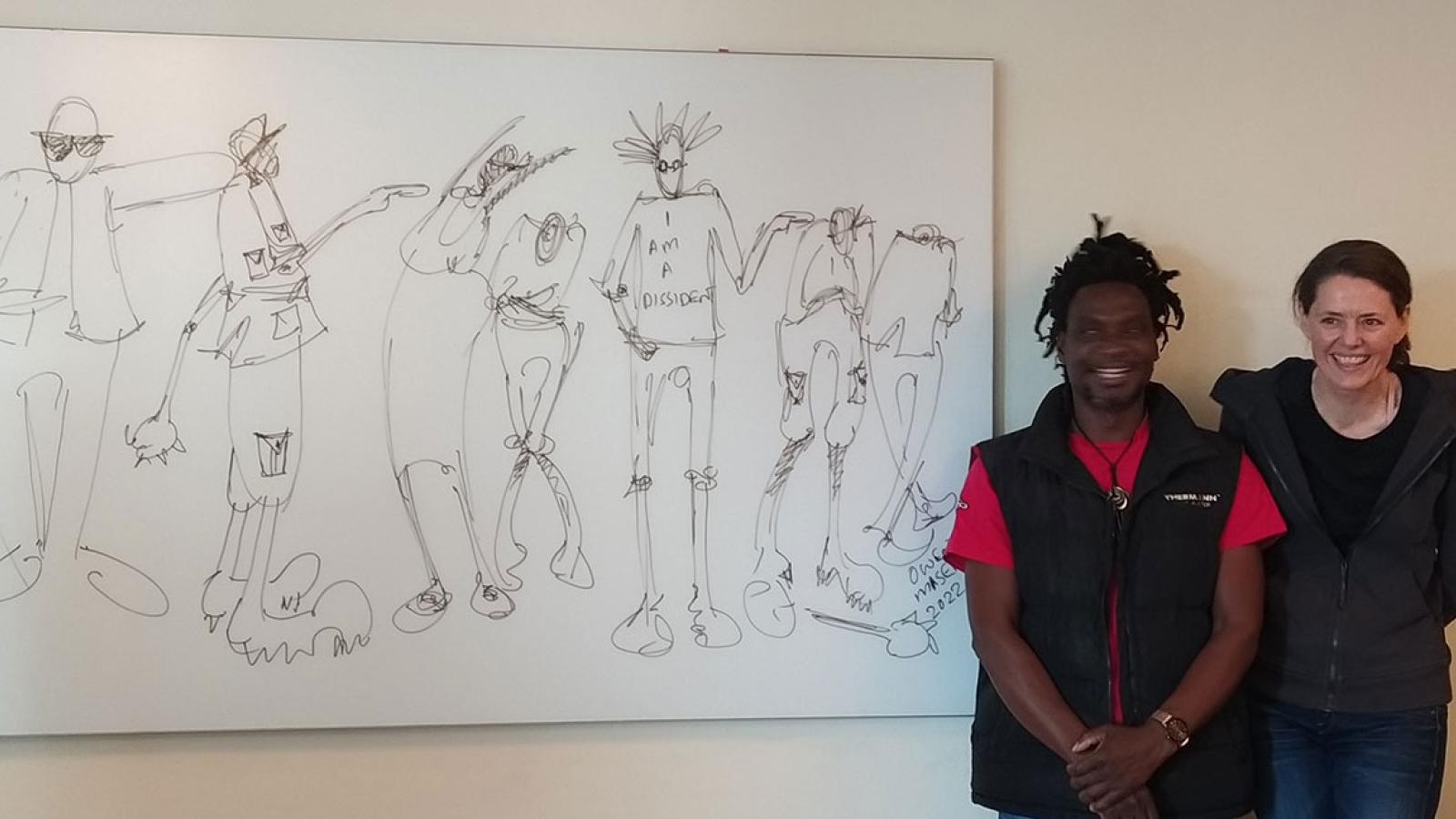

Jocelyn Alexander with artist Owen Maseko, who illustrated her talk.

How do various media tell stories to diverse audiences? Can fiction complement history in explaining nation making? Can we redress the power imbalance between filmmakers and their subjects? ODID’s latest roundtable explored the power of the creative arts to generate new kinds of knowledge. Drawing on footage and illustration, researchers presented a range of innovative, collaborative projects, crossing disciplinary boundaries to harness the arts in development research.

Making the storytellers: collaborative filmmaking as research

Exploring the historic relationship between the moving image and political change in Ghana at the moment of political decolonisation, Dan Hodgkinson uses film in multiple ways throughout his research: as a research tool, as an object of research into the visual language of politics, and as a research output that can appeal to audiences far beyond the academy. Ghana’s decolonisation in 1957 – the first in Sub-Saharan Africa – was an iconic moment across the continent. President Nkrumah immediately launched an ambitious project to transform what it was to be African – how people imagined themselves, their role and their communities. Film was central to the project. Nkrumah established the largest filmmaking facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa, but after a coup in 1966, the new military authorities ended the project, destroying much of the film archive. More was destroyed in the 1990s after Ghana’s film corporation was sold to a Malaysian company, which burnt the archive, citing health and safety reasons. So how can we investigate history when the historical source has gone? By working with the people who made it.

In collaboration with filmmaker Anita Afonu, the project works with the older Ghanaians who pioneered independent Ghana’s film industry. Anita is one of many young Ghanaian artists – including, for instance, Ibrahim Mahama – revisiting this historic era of promise and change to make sense of their current world and the ideals they should live by. Rather than just film interviews with post-colonial filmmakers, The Storytellers follows Anita as she attempts to make her own film using the techniques and style of these early masters – including celluloid film stock and crews. This process brings these old hands back onto the filmsets and into editing suites to show Anita how to make film using their original methods. In this way, The Storytellers provoked rich, varied conversations about their earlier work, nostalgia and humour for the past, and an elusive sense of political purpose that was lost during the successive decades of political malaise. The result is explicitly not a film about the past, but a film about what is at stake in the past for Ghanaians – both young and old – today.

Fiction in history, history in fiction: research collaborations with literary scholars

Building on her research in the 1990s with survivors of state massacres in the Matabeleland and Midlands provinces, Jocelyn Alexander explored how fiction complements social and political history to capture the experience and memory of violent nation-making. Collaborating with literary scholars and artists, she examined three Zimbabwean novels based around “the dissident”, a character who can be interpreted as at the heart of the violence and its justification, but in contradictory ways depending on your perspective. While presenting her paper, well-known Zimbabwean artist Owen Maseko responded with a cartoon illustration of different versions of this character – including an intelligence agent, pulling the strings of a security force operative, pointing the finger at civilians who they identified as dissidents, and a young activist pointing his finger at the security force agent and identifying him and his handlers as dissidents.

The social and political history produced after the state violence in Matabeleland is empirically authoritative, but novels must be read differently and reveal aspects of the experience and legacies of violence that have been obscured. Novelists such as Yvonne Vera work in a space between reality and imagination, creating worlds in relation to experience and memory. In her heavily symbolic, politically opaque writing, dissidents seek solace in ancient patriarchal mythology, and history is not linear, but mythic and entrapping, like a web. Characters avoid the constraints of history writing by pursuing gendered, highly intimate, socially mediated understandings of Zimbabwe’s making.

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s novel House of Stone takes for granted that both the powerful and their victims will manipulate history creatively for their own purposes. She shows how silence, truth and lies tear lives apart, but remain central to producing meaning, identity and community. In these novels, truth inhabits intimate spaces, and seeking it can be both life-destroying and liberating. Jocelyn’s work exposes the limits of history writing and illuminates the gendered social spaces that shape the experience and memory of violent nation-making.

Integrating film into research: lessons from 'Architectures of Displacement'

Given the power of our phones and how used people are to being filmed, integrating film into research is increasingly straightforward. In his project “Architectures of Displacement”, Tom Scott-Smith used film to study seven types of refugee shelter in different locations, exploring their design and rationale, what worked and what did not, and how their creators addressed shelter as a basic human need. This revealed three advantages and three challenges of using film.

In terms of advantages, film enables researchers to communicate vast amounts of information, quickly and to a wider audience. It also conveys the details of a visual phenomenon such as architecture and the way people move through spaces. It can also change interview dynamics in a positive manner, as interviewees on camera appeared to “perform”, as if their words mattered more and would reach larger audiences.

Yet filmmaking also involves an element of fabrication. Editing decisions create a story, juxtaposing images or dubbing background sounds microphones failed to detect. Filmmakers wield great editorial power – for example, making people appear to say things they did not. Where writing indicates edits through ellipses, only trained eyes can detect film edits. Film also requires a complex legal package of image, audio and location rights before formal release. Contributors must sign consent forms waiving their rights, and academics lose intellectual rights over output made using Research Council or university equipment. Reaching a wider audience is also not completely straightforward.

Representative filmmaking: refugee stories in Kakuma

Raphael Bradenbrink also explored the power filmmakers have in editing, through his work in Africa’s largest refugee camp, Kenya’s Kakuma. His research addresses the challenge of using representative stories when researchers try to bring quantitative data alive. The images and voice of refugees are often unrepresentative, decontextualised in political ways for strategic use to influence audiences and elicit specific emotions. Audiences generally see three typical images: refugees as victims, villains or heroes. Although not necessarily untrue, these dominant narratives are not usually representative; rather they are extremes, narrated as if representative. This means people see reality through a distorted lens that eschews the majority experience for what is newsworthy or strategically useful.

In Kakuma, Raphael sought to contextual people’s stories. Most camp residents live on less than $2 a day, but the research portrays people’s lives across a variety of income distributions, rather than the usual extremes – including the rarely represented mid-range, where most people live. Researchers filmed interviews with residents of nine households representing different data points across the range of income distribution, building narratives that contextualise their lives, linking quantitative data and human stories. Importantly, unlike photos, these films capture non-material differences between households, including aspirations and challenges.

Given the power within the editing process, Raphael worked with refugees who had been trained as filmmakers before arriving at Kakuma, drawing on residents’ ideas of how they wanted to be represented. The resulting films prove video is an accessible, versatile medium, not just for gathering material, but for sharing it with participants where articles and books do not allow.

Recognising the knowledge of the future

The concluding discussion further explored issues of power. Refugees can see talking on film as an empowering platform when they have no other outlet. There are also questions of power between written genres. In history writing, interviews can be perceived as interrogation, giving nothing to the interviewee and failing to represent their experience, whereas a novel can show complexity and communicate things that escape social history. In contexts where the truth cannot be spoken in formalised ways, different media allow different kinds of stories to be told.

Filmmaking also presents increasingly complex questions of fact versus fiction. AI will soon produce imagery whose veracity will be impossible to determine, meaning transparency will be key in making credible academic film. And while central mechanisms such as journals establish the authority of the written word, how should we formally recognise visual knowledge? With the increasing use of visual language, we need to rethink what knowledge is.

Shelter without Shelter, Tom Scott-Smith's film drawing on the Architectures of Displacement project, will be released in September, alongside his book, Fragments of Home: Refugee Housing and the Politics of Shelter, to be published with Stanford University Press.

This post draws on an ODID Research Roundtable on Film, fiction and social change held in Trinity Term 2024. ODID Research Roundtables are intended to create productive conversations around shared intellectual interests, methods, and practices in the department. Each roundtable seeks to cut across the department in terms of the seniority of speakers, disciplines, geographical regions, and the location of participants in degree programmes and research groups.